Home Range Size

Certainty styling is being phased out topic by topic.

Hover over keys for definitions:Difference in home range is a relative difference between hominids and non-hominid primates. Simply put, home range is where an animal spends its time, lives, eats, reproduces, travels and dies: the region that encompasses everything an animal needs to survive and reproduce. Obviously, modern (particularly Western) humans have an enormous home range, driving and jetting back and forth across the globe. While this is sociologically interesting, this entry will concern itself with early hominids.

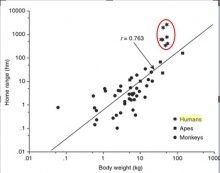

Generally, early humans and hominids have a greater home range than other primates and monkeys (see figure, from Gamble 2013), both in absolute terms and relative to body size. An increased home range allows more access to a variety of food sources and ecological niches. Overall,this increase in home range seems to be related to the search and acquisition of food. Anton and colleagues argue that this increased home range size was indeed related to the exploitation of new ecological niches, dating back to H erectus. They claim that “changes in foraging strategy and body size in H. erectus [were] facilitated by changes in ecosystem structure during the Plio-Pleistocene” (Anton et al 2002), an era was characterized by the rise/prevalence of the large herbivore, among other things, changing hominid diet and behavior. One of the key facets of this change was an increase in home range size to hunt these herbivores. This increased ability to obtain a high fat/energy diet has been hypothesized by many to have helped sustain the larger hominid brain size.

Wheeler argues that early hominid development goes hand in hand with home range size. he argues that the evolution of larger hominids allowed them to “dehydrate more slowly and are able to cover a greater distance each day” (Wheeler 1992), which is quite important in dry areas like the African savannah. Further, Wheeler demonstrates that bipedalism confers similar advantages: “allowing hominids to forage at higher temperatures and over greater distances, while consuming less food and water, than quadrupeds” under all conditions examined (Wheeler 1991). The evolution of tool use undoubtedly also aided in the expansion of home range, particularly the development of water storage and the ability to preserve food.

This increased home range is related to human’s ability to inhabit (and consequently exploit) multiple, diverse areas, adapting to exploit more, different areas within a short time span, rather than exploiting a single niche (as would be the case with a small home range). Human tool use and their larger group size, as well as the Plio-Pleistocene’s increase in calorically dense food resources and hominid advances in food attainment seems to allow for this large home range (Finlayson 2009). Essentially, the argument as to why home range increased in non-human primates is intrinsically intertwined with a suite of other more-or-less uniquely human properties. Hominid ability to have a larger home range, encompassing multiple biomes both supports and is supported by things such as water storage, cooking and group size as well as ecological changes.

References

-

-

Neanderthals and Modern Humans: An Ecological and Evolutionary Perspective, , p.113-117, (2009)

-

An ecomorphological model of the initial hominid dispersal from Africa., , J Hum Evol, 12/2002, Volume 43, Issue 6, p.773-85, (2002)

-

The thermoregulatory advantages of large body size for hominids foraging in savannah environments, , 10/1992, Volume 23, Issue 4, p.351 - 362, (1992)

-

The influence of bipedalism on the energy and water budgets of early hominids, , Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 21, Issue 2, p.117-136, (1991)