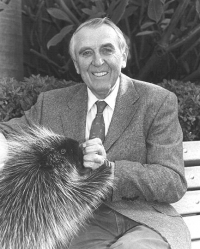

Kurt Benirschke

Benirschke, among the earliest faculty at UC San Diego School of Medicine, famously combined interests in human and animal biology, advancing comparative pathology and the preservation of endangered species.

Kurt Benirschke, whose medical and scientific interests spanned the animal kingdom and likely saved more than a few species from extinction, passed away September 10, 2018. He was 94.

“Dr. B” or “KB”, as he was affectionately called, joined the faculty of University of California San Diego School of Medicine in 1970, shortly after the school opened. He served nearly a quarter of a century as a noted pathologist, geneticist and expert on the placenta and reproductive systems of humans and myriad mammalian species. He became internationally known for his successful efforts to create the world’s first “frozen zoo.”

Benirschke was born in the small northern German town of Glückstadt in 1924. He received his medical degree from the University of Hamburg in 1948 and immigrated to the United States in 1949.

During an internship at Holy Name Hospital in Teaneck, N.J., Kurt met his future wife, Marion, who was a nurse at the hospital. Benirschke received residency training in pathology at Harvard Medical School and, in 1955, became a pathologist at Boston Lying-in Hospital, one of the first maternity hospitals in the United States, now part of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. It was there that he became particularly interested in the biology of the placenta and reproduction.

From 1960 to 1970, Benirschke served as chair of the Department of Pathology at Dartmouth Medical School, further exploring placental pathology and comparative reproductive pathology. He investigated how viruses are passed from mother to fetus and the phenomenon of chimerism, in which an individual possesses two or more complete sets of genetic material. He also explored why mules are sterile and twinning in armadillos and marmoset monkeys, which led to a lifelong love affair with South America and its wildlife, particularly the tagua or Chacuan peccary in Paraguay.

In 1970, Benirschke was invited to join the faculty of UC San Diego School of Medicine and moved his family to San Diego. (UC San Diego had just debuted its first class of students in 1968.) He established a genetics laboratory, ran the autopsy service for the university hospital and almost immediately became an influential voice and figure in the world of animal conservation.

In August of 1970, Benirschke became involved with the San Diego Zoo, lobbying for the creation of a novel “cell bank” to preserve the eggs, sperm and other tissues of endangered species. “A number of mammals and other species are going to become extinct in the next decades, all efforts notwithstanding,” Benirschke wrote to leaders at the San Diego Zoological Society. “This is of very great concern to me and I hope that we can somehow proceed. I am going to summarize what I can contribute to the subject.”

Benirschke believed the San Diego Zoo would be an ideal home for a so-called “frozen zoo,” a repository containing reproductive tissues from animals around the world, from rhinos and whales to apes and antelopes, stored at temperatures approaching minus -200 degrees Fahrenheit. At the time, there was no technology yet available to effectively thaw, study and revive frozen eggs and sperm, but Benirschke, quoting American historian Daniel Boorstin, said “You must collect things for reasons you don’t yet understand.” His words would prove prophetic as technologies subsequently emerged, advancing conservation science.

In 1979, the Zoological Society established CRES, the Center for Research of Endangered Species, which Benirschke led until 1985, when he joined the Zoo’s board of directors. Today, the renamed San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research is the largest of its kind, with more than 10,000 living cell cultures, oocytes, sperm and embryos representing nearly 1,000 taxa, some extinct and many severely endangered.

Benirschke moved freely between human medicine and animal medicine, considering lessons learned to be universal. A 1984 tribute book to Benirschke, written by 50 of his colleagues, is titled “One Medicine.” Kurt was always busy: teaching courses, conducting research and lecturing around the world. From 1976 to 1978, he served as chair of the Department of Pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and played a key role in the creation and success of the Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny (CARTA).

He formally retired as professor emeritus in 1994 but remained active as a consultant to the autopsy service, in the field overseeing a breeding facility in Paraguay for a newly discovered species of peccary and in publishing scholarly papers.

Since 1994, the departments of Pediatrics and Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences have presented the annual Kurt Benirschke Lecture, featuring international experts on topics relevant to biology and procreation.

Benirschke produced more than 500 scientific publications and more than 30 books, including the authoritative text “Pathology of the Human Placenta,” now in its sixth edition. He received numerous honors and awards, including the Virginia Apgar Award in 1998 from the American Academy of Pediatrics. He was a member of many scientific societies, including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

He is survived by his wife, Marion, and three children: Stephen Benirschke, a surgeon and professor of orthopaedics and sports medicine at University of Washington; former San Diego Charger Rolf Benirschke; and Ingrid Benirschke-Perkins, community relations director for CARTA at UC San Diego.

From UC San Diego Campus Notice: http://adminrecords.ucsd.edu/Notices/2018/2018-9-14-1.html